I’ve been struck with a patch of Internet curmudgeon syndrome of late: spending too much time on Facebook probably. One of the ongoing themes of my work as a digital rhetorician is the observation that we do not know how to behave in digital media ecologies. That observation is not a starting point for a lesson on manners (though we certainly get enough of those too!). Instead, it’s a recognition of the struggle we face in developing digital-rhetorical practices.

Those of us who were online in the 90s (or earlier) certainly remember flame wars on message boards and email lists. This was the start of trolling, a familiar behavior to us all which in some respects I think has mutated and become monetized as clickbait. Of course trolls are just looking to get a rise out of you. It may be hard to tell the difference from the outside, but some of these incendiary conversations were genuine disagreements. I know I was part of some very heated exchanges as a grad student on our department email list. Eventually you realize that you’re not in a communication situation but instead you’re part of a performance where the purpose is not to convince the person you’re putatively speaking to but to make that person look foolish in front of a silent audience who has been subjected to your crap by being trapped on the same email list with you. That changes one’s entire rhetorical approach, especially when you realize that the bulk of that captive audience isn’t captive at all but simply deleting emails.

In some respects that practice lives on. I am still on a department email list, and sometimes it gets heated. It’s not very productive but at least it’s limited in scope.

In the early days of this blog, I wrote some fairly strident stuff. These days I still offer views with which many would disagree, but the tone has mellowed, perhaps its middle-age. However, I see around me, mostly through Facebook, the continuing intensification of flaming rhetoric. In the good-old, bad-old days, I used to think that flaming happened because people were at a distance from one another. Because there was never any danger of physical violence, a certain limit on the riskiness of invective was removed. Today though we have the long-tail, echo-chamber strengthening of that feeling. Not only can I be as agonistic as I please without physical threat but I can find others who will agree with me and double-down on the whole business. Needless to say this happens across the political spectrum. Add in the clickbait, Facebook capacity, and one gets rhetorical wild fires.

An academic example of this. Perhaps you saw the recent piece about the liberal professor afraid of his liberal students, or the following piece about the liberal professor who is not afraid of her liberal students. All of this business is driven by serious challenges in higher education. There is the declining authority and power of faculty. This comes in a lot of forms. Most notably it is the disappearance of tenure and the disempowerment of tenure where it still exists. In more general terms though it is also the dilution of authority as opinion, especially in anything that is not empirical, though obviously even science is challenged in certain areas.

There is also this conversation about “triggering,” which I won’t go into here, except to say that in all this rhetoric it often seems difficult to differentiate between someone who has a mental health issue related to a traumatic experience and someone who is unhappy, uncomfortable, or offended. Given that current digital rhetoric practices seem to allow for only two positions, “like” or “I’m offended,” it’s quite hard to avoid the latter, while the former deserves real consideration.

Anyway, I’m not interested in getting into that conversation in substance here. My point is simply to wonder aloud what the rhetorical purpose of such “communications” might be. I use the scare quotes because I’m not sure they are communications. They are expressions. Deleuze and Guattari make this point in A Thousand Plateaus. In their discussion of order-words, collective assemblages of enunciation, incorporeal transformations and such, we encounter the autonomous quality of expression, which is to say that expression obeys its own laws, independent of both the speaker and the listener, as well as whatever other larger network or cultural situation might be in effect.

It is clearly possible to get symbolic expressions to do work. In print culture we created elaborate institutions and genres to do so. The university is one of the best and most successful examples. That’s not to say that it was perfect. Far from it! But it is a good example of how one instaurates (to use one of Latour’s terms) a communicational assemblage from a media ecology.

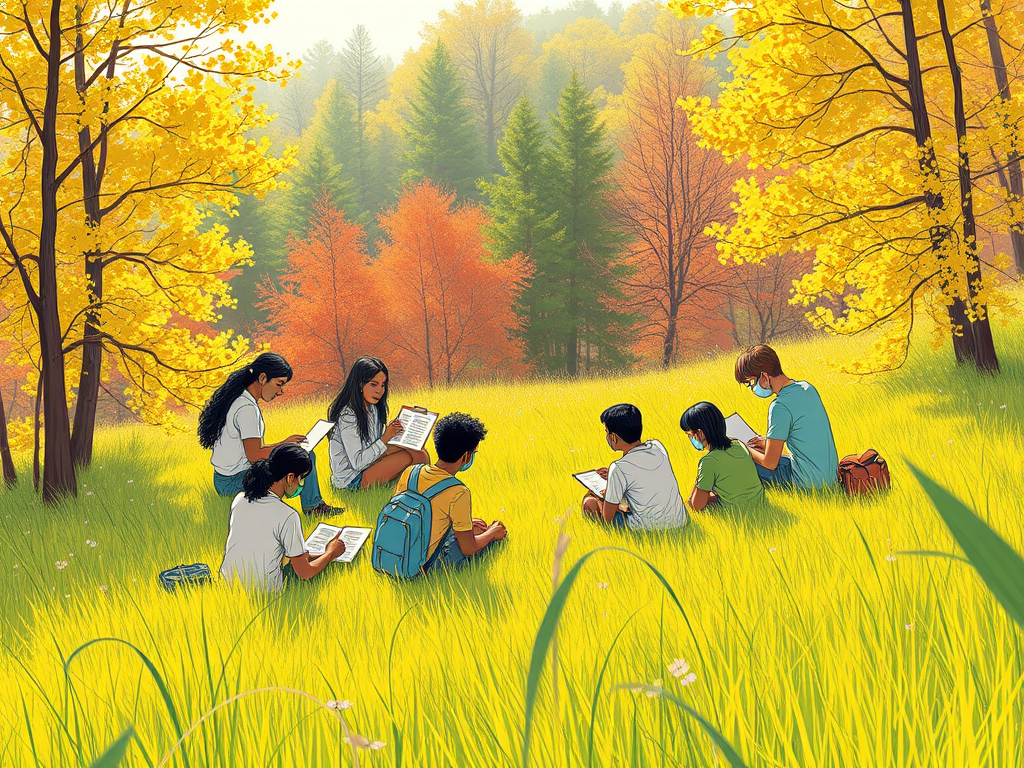

We really need to build new genres, which means new communities, networks, assemblages, activity systems, however you want to think of it. On some level I imagine that’s what we’re trying to do here, but I’m not very satisfied with the results so far. This strikes me as some of the central work of digital rhetoric. Not to be prescriptive about future genres, but to facilitate rhetorical understanding of current genres, to investigate alternate rhetorical capacities, and perhaps to experiment.#plaa{display:none;visibility:hidden;}

Leave a comment